Ramblings

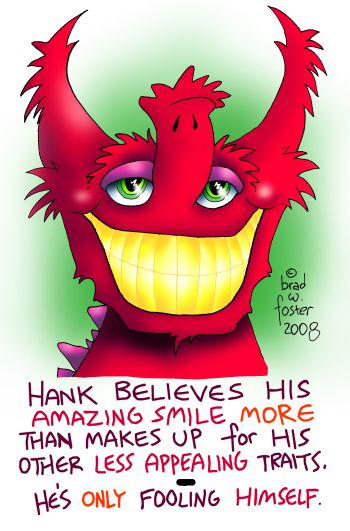

Once again, a Brad Foster cartoon that's too insanely detailed for the 1.24" square art spot in the printed Ansible....

Not A Review. Hard to believe it began so long ago: I was bowled over by John Crowley's Aegypt – since retitled The Solitudes, with "Aegypt" becoming the overall series name – when it appeared in 1987. Love & Sleep followed in 1994, Daemonomania in 2000, and the concluding Endless Things in 2007. In November 2008 I read them all in sequence, one house of the zodiac (each volume is divided into three) per evening: Vita, Lucrum, Fratres; Genitor, Nati, Valetudo; Uxor, Mors, Pietas; Regnum, Benefacta, Carcer. What to say? It is, of course, beautifully written. The elusive mechanism of secret history, in which magic is always something that happened then and has vanished even from the past of the mundane now, is endlessly fascinating – and sometimes convoluted with what Douglas Hofstadter calls Strange Loops, as when Doctor Dee (in the historical novel-within-the-novel) unravels ciphers to reveal the opening words of the first book's prologue and initial chapter, or when he peers into a scrying stone to meet the eyes of the child who in the outer novel is examining the "same" stone. It seems entirely in keeping – especially remembering the high density of Alice references in Little, Big – that Giordano Bruno should confidently quote Humpty Dumpty. But can Bruno be saved from the wrath of the Vatican? Yes, and no: Endless Things repeatedly references the Y-shaped bifurcation of history which on Terry Pratchett's Discworld is invariably termed the Trousers of Time. The grass is always greener down the other path. Even while turning away from the high fantasy of the inner book, and writing of deeply divided characters, Crowley shows a Chestertonian delight in the magic of the mundane. One telling point, perhaps indeed the central one, is his gentle indication that the extraordinary irruption of a unique messenger into our universe in the first book's "Prologue in Heaven" is – viewed in astrological terms – no more and no less than the story of every human birth. If I ever write at length about this tetralogy I'll need to read them all again and this time take full and proper notes, which will be a pleasure; meanwhile, Michael Dirda has done an excellent job in this review. Thank you, John Crowley.

Why I'm Not Busy Writing A Book. I thought I had a deal for a nonfiction project, but it fell through during what I expected to be routine negotiation. The clause I and my agent didn't like was the one that explained that on delivery, for any reason or none ("Publisher's sole discretion"), the publisher was free not only to ditch the book but to claw back the entire initial advance, leading to the exciting prospect of six months' work for zero return. We insisted on some sort of softening here, even "approval shall not be unreasonably withheld". The publishers – or rather, their legal department – threw a hissy fit and walked out with the startling non-sequitur that they couldn't work with an author who refused to accept editorial direction. Well, no, not when the directive is "Shut your eyes, Luke, and sign the Clause."

The Thog Files. More items that for one reason or another didn't seem quite right for Ansible. • Dept of Social Comment. "When the girl fainted, and the father took to kicking her, the boy ran to the window and screamed, as some jungle animal caught in a trap screams. His eyes crossed suddenly, he foamed at the mouth. Epileptic himself, he shrieked as his epileptic father, married by the Church to a diseased woman, cracked the young head open at the base of the skull with the leg of a chair." (Joan Conquest, With the Lid Off, 1935) – quoted in a Thoglike selection from 1930s book reviewing in James Agate's Ego 7 (1945). But I don't quite trust Agate not to have improved a little on the original. • Did The Earth Move For You? Dept. "Her hands were working on me, and I was free of my pants and suddenly sinking into her, all my sensations lost in my sex for a moment. feeling like a traveller who's stumbled into a soft warm cleft in the ground, slid into it as if it were quicksand, completely engulfed and not caring: discovering an exquisite loss of self there... " (John Shirley, The Black Hole of Carcosa, 1988) – thanks to Brian Ameringen.

Commonplace Book. Steve Sneyd sends another entry for the Talking Squid (if not Talking Squids in Outer Space) dossier: "Charles Cameron Kingston, a premier of South Australia in the 1890s, accused an opponent of being 'a gruesome ghoul with lips reeking with mendacity and foetid with malice; a forensic compound of squid and skunk.'" (Independent, 5 July 2008). • A tasty bookseller's description, via Brian Ameringen: "John Meade Falkner: The Lost Stradivarius. A very fine, very clean and unread copy of this rare treasure, in flawless boards, a spine as tight and wholesome as a meat pie in a chastity belt, clean, virginal, untouched pages and an unmarked, clean dustjacket. Almost AS NEW; includes dustjacket." • Hazel, who is deeply engaged in family history research, was unimpressed by this tactful example: "Mr. Robert de Forest wrote a genealogy of the de Forest family ($7.50, 2 vol.), but, for fear of offending the present generation, refrained from putting in the dates of their births." (Edmund Wilson, A Prelude, 1967)

The Letter Column

Brian Ameringen remembers the late Forrest J (Forry) Ackerman, master punster:

I should tell you the story of an exchange I had with him at Confiction. I pointed out that we are all human and asked if he had considered the music to be played at his funeral ... he hadn't. So I commended for his interest Fauré's Requiem... I think he appreciated the suggestion – but I didn't hang around to find out – just in case!

Richard E. Geis introspects:

Thanks for Ansible #255. I was intrigued by Phil Farmer's 25-year-old suggestion that body parts might have souls. Of course! That explains my entire porno career – my cock has a surplus soul which, over the decades, has taken over my entire body, thus explaining why I look at porn vids 23 hours per day and leer at every pretty girl in sight. Or is it only my fingers which have a soul, explaining why I only write porno letters for Hustler's Fantasies. Or why I began masturbating at age 6. How lucky I've been! Think of my life if my soul had been assigned to my big left toe.

Simon R. Green muses:

The whole Hadron Collider thing wouldn't worry me so much, if I hadn't heard the countdown; the guy in charge stopped part way through to giggle. I really don't want someone in charge of such a potentially dangerous operation, who is prone to the giggles. I can't help feeling the word "Oops!" can't be far behind."

Diana Wynne Jones tells horror stories of her husband's misadventures in the Kitchen of Doom. I'd impulsively sent her a spare copy of The SEX Column, and ...

Many, many thanks for the book. It was delivered, in the manner of such jinx things, to Number 11. It arrived in somewhat spectacular circumstances. John, who is a polio victim, now suffers from PPS – which basically means that the beastly disease comes BACK when you are in your seventies – and his legs only just hold him up. He falls, and fell that evening when our neighbour came cheerfully round to redeliver your book. He arrived to find John sitting against our fridge, having wiped off all the fridge magnets and covered the kitchen floor with broken crockery and cold potatoes and narrowly missed landing on an upended steak knife. He was aghast, poor man. Once down, John can't get up, so I had to ask this poor man to help me. I may say that we were markedly inefficient at this, me and the neighbour, and could only watch as John crabbed about, putting his hands in cat dishes and backing his way into a chair. But we did succeed in helping him into the chair.

[Later:] John has some kind of 'flu, which accounts for his problems, because he won't admit to it. He arrived in our kitchen a few days back, announcing that he would just make himself a cup of tea – whereupon both I and Chris Bell (who happened to be there) rose up, crying in unison, 'Oh no you won't!' This was just after the Great Catfood Episode, in which John fetched a small block of cheese from our fridge. The cheese fell from his nerveless grip and hit the corner of a cat saucer filled with small brown pellets of catfood. The result was like an explosion in a Tiddleywinks factory. Catfood all over kitchen, dining room and the front hall. John recoiled from it and, for good measure, trod on the cheese. We are still finding small brown pellets in unlikely places.

[Later still:] And if required I will supply another rant on how USELESS doctors are about the after-effects of polio, which they appear to conflate with bubonic plague: ie it happened sometime in the remote past and is no concern of theirs. I got angry enough to tell one doctor that he was too young for his job.

Fred Lerner's reply when I sent him a link to this sign:

At the Bear Pond Bookstore in Montpelier, Vermont, there used to be two directional signs hanging overhead, one reading "Truth" and the other "Beauty". Every few months management would swap their locations.

Taras Wolansky sent a newspaper extract which could well have given us Thog's Department of Vampire Toyboys if only the writer had specified which book of Stephenie Meyer's "Twilight Saga" she was quoting from:

I read the first two Twilights, searching for the key to their success. [...] The attraction is clearly the vampire hero, who is a perfect gentleman, eternally faithful and – as the author points out repeatedly – quite a hunk. ("He lay perfectly still in the grass, his shirt open over his sculpted, incandescent chest, his scintillating arms bare ... A perfect statue, carved in some unknown stone, smooth like marble, glittering like crystal.")

Before you make fun of this, I want you to seriously consider whether you're interested in denigrating people who spend their leisure time actually reading books rather than watching "America's Got Talent." (Gail Collins, New York Times, 12 July 2008)

Random Reading

Mary Gentle, 1610: A Sundial in a Grave (2003). An enjoyably swashbuckling homage to Dumas and his Musketeers, with familiar genre elements – including swordplay, cross-dressing, assassination, headlong pursuits, impersonation of strolling players, and conspiracy against the royal succession – given an sf rather than fantasy frisson by the introduction of a mathematical predictive technique (allegedly pioneered by Giordano Bruno) that's distantly related to Isaac Asimov's psychohistory. Here the Hari Seldon figure is English astrologer Robert Fludd, who has charted Earth's future and sees a comet-impact disaster in the 22nd century. To unite humanity against this, he dubiously reasons, we need a strong English monarchy and lots more of the Divine Right of Kings. Therefore history must be reshaped by getting rid of King James I as a first step towards eliminating the execution of Charles I from the timeline. What I couldn't quite swallow was Fludd's ability to predict, through many previously calculated mathematical iterations, a future opponent's every possible reaction in a duel – enabling this untrained scholar not only to humiliate an expert swordsman (the hero, or antihero) but to teach his hirelings to do the same at will. Hmm! But it makes for a rousing story, spiced with mild sexual perversity. Oh, and besides the customary adventuring across France and England there's an excursion to Japan with profound effects on that country's history....

Gerald Heard / H.F. Heard, A Taste for Honey (1941), Reply Paid (1942) and The Notched Hairpin (1949). Sherlock Holmes famously retired to keep bees, and the first of these offbeat detective novels – delicately flavoured with Holmes pastiche – is a clash of ruthless apiarists with the hapless narrator caught in between. One is a mad scientist who, without much motive beyond general homicidal enthusiasm, has bred lethal killer bees which can follow airborne trails of scent (the word "pheromone" is not actually used) to suitably tagged and thus doomed victims. His opponent has retired from a life of "estimating human intelligence not by its books or words but by its tracks", and has studied bees so effectively as to devise means of subduing them with amplified but inaudible sounds – the word "ultrasonic" is not actually used. Quite science-fictional in a borderline way. Even when the duel is over, Heard teasingly refrains from dropping the name "Sherlock Holmes". In the original US editions the aged sleuth is known only as Mr Mycroft; this hint was apparently thought too broad for readers in Britain, where he became Mr Bowcross. Either way he is lean, energetic, and clearly not intended to echo Conan Doyle's vastly corpulent and lazy Mycroft Holmes. This was lost on at least one North American publisher which billed all three books as "The Mycroft Holmes Mysteries" and prefaced them with an Encyclopedia Sherlockiana description of Mycroft, though none of Sherlock.

Reply Paid also has fantastic touches, including the consultation of a psychic medium to crack the first part of a tricky cipher clue, and a new forensic theory of teeth, which here have internal rings exactly analogous to tree-rings and record the various traumata of life. If my teeth had been steadily growing over the years by accretion of new layers, I think I'd have noticed. The central McGuffin proves to be a extravagantly radioactive meteorite in the Utah desert which, having brought its finder to a sticky end, promptly evaporates into pure energy and provokes speculations about the asteroids having once been a planet or two planets – so far, so familiar – where "some mad form of life must have monkeyed with matter's make-up". Atomic-war theories of asteroid formation were commonplace after 1945 (for example in Robert A. Heinlein's 1948 Space Cadet: "artificial nuclear explosion ... they did it themselves"), but this was 1942. Alas, after these quasi-sf excitements The Notched Hairpin is a rather dull locked-garden murder mystery, combining devices all too well known from such classic detections as G.K. Chesterton's "The Oracle of the Dog" and Carter Dickson's The Judas Window. It feels like a short story padded to book length with a lot of talk, including one of those protracted flashbacks in which – as in some of the Sherlock Holmes novels – the murderer's and victim's shared background is most laboriously explained.

Terry Pratchett, Nation (2008). A standalone novel, notionally for younger readers – the Carnegie Medal win is blazoned on the British hardback's front cover – but a long way from being childish. Discworld and especially its central city Ankh-Morpork have grown increasingly ramified and labyrinthine through many sequels; this alternate-nineteenth-century adventure has an effective, hard-edged simplicity. Somewhere in the Great Southern Pelagic Ocean our young hero Mau, fresh from the lonely ordeal of becoming a man, returns home to find his tiny island Nation destroyed by a great wave. Nothing is left but vegetation, pigs, birds, angry ancestral voices, and – on a stranded ship of the British Empire – a white "ghost girl" called Ermintrude, who quickly takes the opportunity to reinvent herself as Daphne. Droll communications problems are only the overture. Refugees soon begin to straggle in. How to feed a baby that needs milk? Mau's solution is heroic, comic and horrific at the same time. How to deal with the sick and wounded? Daphne works her way resolutely through the Manual of sea doctoring, up to and including the sawing off of legs. How to tackle an invading cannibal tribe now led by a British seaman who is one of Pratchett's nastiest smiling killers? (He's reminiscent of Carcer in Thief of Time, but with a better gift of the gab.) The ultimate challenge is that of being rediscovered by Britain itself, which has marked the Nation on its charts – in red, claimed for the Crown – as one of the lowly Mothering Sunday Islands. But the Nation has its surprises, not of any expected kind, for the Empire. Without any lessening of comedy, Pratchett sets up a tension between various loyalties – to individuals, countries, governments, history and truth – which shapes a highly effective finale and aftermath. Funny, thoughtful, touching ... and with land-dwelling, tree-climbing octopi too!

Charles Stross, Saturn's Children (2008). I confess to slight nervousness about a Stross homage to, or send-up of, Robert A. Heinlein, but this cheerful romp works rather well. Our heroine Freya echoes the title character of Friday, not only in name but by being an artificial person – in fact a robot concubine who's out of a job because the human race is extinct – despatched on a smuggling mission whose organic payload is concealed within her own body. At one stage, joyously echoing "The Number of the Beast", her faulty nipple goes spung! Also very much in late Heinlein mode, there is good sex with an older male, a robot Jeeves who is in fact of more recent construction than Freya but was built to project middle-aged reassurance. The experience of having one's free will overridden by a "slave chip" is reminiscent of being slug-controlled as in The Puppet Masters, and (reverting to Friday) the ending sees the most likeable characters outward bound on a starship. Stross stitches all this into a jolly adventure plot – with such Perils of Pauline setpieces as Freya being tied to Mercurian railway tracks along which an entire terminator-following city is rolling inexorably towards her – and is characteristically liberal with what the late Bob Shaw called "wee thinky bits". Gradually we begin to appreciate the horror with which a robot-peopled Solar System regards the possibility of recreating beloved humanity after the fashion of Jurassic Park: the slave conditioning inherent in those Laws of Robotics would instantly kick in, marking the end of freedom and independence. No wonder the Pink Police are constantly on the alert for this "Pink Goo" threat. We have met the enemy and he is us.

Also read: Peter Dickinson, The Lion Tamer's Daughter (1997 in collection, solo publication 1999) – effectively creepy short YA novel, set in contemporary Britain and revolving around two girls who are in some ways the same person: doppelgängers, mirror images, dreaming one another's dreams. The obvious solution of identical twins separated at birth is ruled out. It seems terribly important that they shouldn't meet, and equally vital that they should; the dilemma resolves through an understated, elusive touch of fantasy. • Cory Doctorow, Little Brother (2008) – surely his breakthrough novel, engaging fiercely with the present-day encroachments on civil liberties that he chronicles with such passion at BoingBoing. The young hero gets all too believably maltreated by US Homeland Security and resolves to fight back with net-savvy stealth measures: there's something of the Heinlein YA novels (though perhaps more of Neal Stephenson's Cryptonomicon) in his engagingly didactic info-dumps about life, encryption and everything. Compulsively readable. • Janet Kagan, Mirabile (1991) – read with a faint sense of guilt at not having done so before this author's untimely death in 2008. Linked stories based on a daft colony-world premise whereby massive redundancy has been packed into Earth-sourced DNA to save space on the generation starship. Now any animal or plant may on occasion produce a quite different species that may have been lost and may be desirable. Or not – as when the daffodils seed cockroaches. The gently comic episodes get better as they go along. Lively and fun. • Alan Moore, Rob Leifeld, Gil Kane, Judgment Day (2003) – random acquisition at Novacon, on the basis that a graphic novel scripted by Alan Moore couldn't be bad. Ho-hum. Apparently Moore was brought in to turn around or relaunch a comic about a superhero group called Youngblood (which I'd never heard of), and began by killing one of them off, framing another, and staging a murder trial that features a plethora of mighty-thewed and/or vast-bosomed witnesses in skintight garb. Folded into this are somewhat repetitive flashbacks about a magic talisman which proves to be a History of Reality that can be rewritten or amended – I loved the rampant metafictionality in Promethea but somehow this left me cold. You can't win them all. • Alastair Reynolds, Galactic North (2006) – a collection of six stories linked to the "Inhibitors" sequence, plus an Afterword. Reynolds has built a good reputation for hardish-physics sf (e.g. keeping the interstellar travel strictly relativistic), but some of the most memorable and disturbing images are of biological grotesquerie verging on outright horror.